Matsuo Mine in Its Heyday

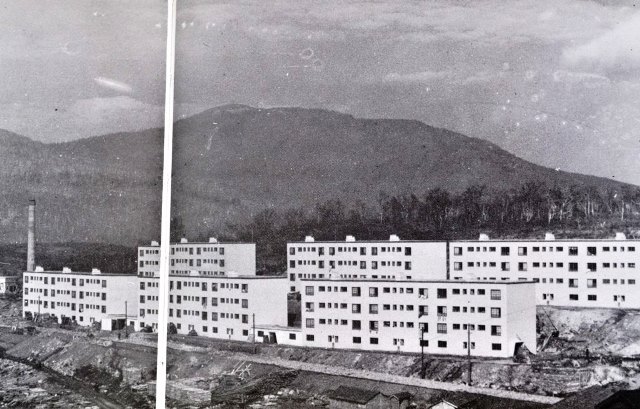

In the early decades of the twentieth century Matsuo Mine in the Hachimantai mountains of northern Iwate Prefecture was not only the most productive sulfur mine in all of Asia, it was also hailed as a model of community living. The mine was founded in 1914. At its height in the mid-1950s it employed 4,900 workers, housing 15,000 people in modern, four-story ferroconcrete apartments built with unprecedented luxury features of the time such as flush toilets and boilers for central heating. There were schools, a large-scale hospital, and a movie theater. Workers’ salaries were well above the national average, and with company policy stipulating that no liquor stores or bars operate on the mountain, the family-oriented community that thrived here at nearly 1,000 meters’ elevation came to be hailed a “paradise above the clouds.”

The sulfur and iron sulfide ore extracted at Matsuo Mine were used in a myriad of products both industrial and consumer-oriented: fertilizers, insecticides and fungicides, adhesives, rubbers, rayon and other fibers, albums, candles, matches, film cases, ping-pong balls, rubber bands, and more. From the mid-1930s Matsuo met 80 percent of the domestic demand for sulfur and even exported overseas. But as post-World War II policies of economic liberalization stiffened competition with cheaper products from abroad, and sulfur became recoverable at low cost as a byproduct of oil refinement and other hydrocarbon processes, the old paradigm of extracting sulfur from volcanic regions became obsolete.

The Beginning of the Collapse

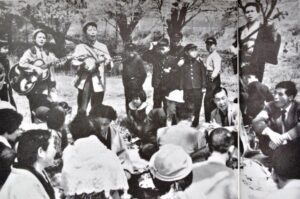

Matsuo’s “paradise” effectively came to an end in 1969. A wealth of artifacts and documents relating to the community that thrived on the mountain in its heyday is housed at the Matsuo Mine Museum in Kashiwadai, a reference facility dedicated to the mine’s history, beginning with the first experimental excavations in 1888. The exhibits (captioned mostly in Japanese only) address the nature of the mining and

refinement processes and show how various technologies and work methods improved over the years. Rail transport, for example, progressed from hand- and horse-powered carts to gas-powered cars, then steam locomotives and finally electric operations. The museum also covers the recreational side of life on the mountain, from residents’ portable gramophones and slide projectors to their chamber orchestra, home parties, chanoyu tea gatherings, and other cultural pursuits. Among the scores of artifacts on display are a pair of silk bed socks used by Emperor Showa in 1954 when he stayed at the site, and a 25-ton locomotive introduced to the works after the railway was electrified in 1951.

Following the 1969 folding of Matsuo Mine, schools on the mountain closed in 1970. The wooden apartments that had housed more than 1,000 residents were burned down in 1972 and 1973. The hospital building continued to be used by Gakushuin University as a satellite facility until 2006 when it, too, was razed. Of the mining community’s former glory, today only the empty skeletons of the ferroconcrete residences remain. These crumbling edifices are deemed unsafe and are off-limit to visitors, but can be seen and photographed from the roadside along the Hachimantai Aspite Line.